The Nikkel-nickel Family of Prussia, Russia, America and Canada

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | lustrous, metallic, and silver with a gilded tinge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard diminutive weight A r, std(Ni) | 58.6934(four) [1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickel in the periodic tabular array | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diminutive number (Z) | 28 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grouping | group 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period four | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d8 4s2 or [Ar] 3dix 4s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, xvi, 2 or ii, viii, 17, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Concrete properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase atSTP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1728 K (1455 °C, 2651 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3003 Chiliad (2730 °C, 4946 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (nearr.t.) | 8.908 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (atgrand.p.) | 7.81 yard/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 17.48 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 379 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tooth oestrus capacity | 26.07 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, −1, 0, +1,[2] +ii , +3, +4[3] (a mildly bones oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.91 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diminutive radius | empirical: 124 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 124±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 163 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound sparse rod | 4900 g/s (atr.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 13.four µm/(one thousand⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal electrical conductivity | 90.9 W/(g⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 69.iii nΩ⋅one thousand (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | ferromagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young'south modulus | 200 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 76 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 180 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 4.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 638 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 667–1600 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-02-0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Axel Fredrik Cronstedt (1751) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Principal isotopes of nickel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nickel is a element with the symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel belongs to the transition metals and is difficult and ductile. Pure nickel, powdered to maximize the reactive surface area, shows a significant chemical activity, but larger pieces are slow to react with air under standard conditions considering an oxide layer forms on the surface and prevents further corrosion (passivation). All the same, pure native nickel is institute in Earth'southward crust only in tiny amounts, normally in ultramafic rocks,[iv] [5] and in the interiors of larger nickel–iron meteorites that were not exposed to oxygen when exterior World's atmosphere.

Meteoric nickel is constitute in combination with iron, a reflection of the origin of those elements as major end products of supernova nucleosynthesis. An iron–nickel mixture is thought to compose Earth's outer and inner cores.[6]

Apply of nickel (as a natural meteoric nickel–atomic number 26 alloy) has been traced as far back equally 3500 BCE. Nickel was start isolated and classified as a chemic element in 1751 by Axel Fredrik Cronstedt, who initially mistook the ore for a copper mineral, in the cobalt mines of Los, Hälsingland, Sweden. The element'due south name comes from a mischievous sprite of German miner mythology, Nickel (similar to Former Nick), who personified the fact that copper-nickel ores resisted refinement into copper. An economically important source of nickel is the iron ore limonite, which often contains 1–2% nickel. Nickel'southward other important ore minerals include pentlandite and a mixture of Ni-rich natural silicates known as garnierite. Major production sites include the Sudbury region in Canada (which is idea to exist of meteoric origin), New Caledonia in the Pacific, and Norilsk in Russia.

Nickel is slowly oxidized by air at room temperature and is considered corrosion-resistant. Historically, information technology has been used for plating iron and contumely, coating chemical science equipment, and manufacturing sure alloys that retain a high argent smoothen, such as German language silvery. Virtually 9% of earth nickel production is still used for corrosion-resistant nickel plating. Nickel-plated objects sometimes provoke nickel allergy. Nickel has been widely used in coins, though its ascension price has led to some replacement with cheaper metals in contempo years.

Nickel is 1 of four elements (the others are iron, cobalt, and gadolinium)[7] that are ferromagnetic at approximately room temperature. Alnico permanent magnets based partly on nickel are of intermediate strength betwixt iron-based permanent magnets and rare-earth magnets. The metal is valuable in modern times importantly in alloys; well-nigh 68% of world production is used in stainless steel. A further 10% is used for nickel-based and copper-based alloys, seven% for alloy steels, 3% in foundries, 9% in plating and four% in other applications, including the fast-growing battery sector,[8] including those in electric vehicles (EVs).[nine] As a compound, nickel has a number of niche chemic manufacturing uses, such as a catalyst for hydrogenation, cathodes for rechargeable batteries, pigments and metal surface treatments.[10] Nickel is an essential nutrient for some microorganisms and plants that have enzymes with nickel as an agile site.[11]

Properties

Atomic and concrete properties

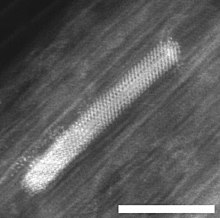

Nickel is a silvery-white metal with a slight golden tinge that takes a high smoothen. Information technology is one of only four elements that are magnetic at or nearly room temperature, the others being atomic number 26, cobalt and gadolinium. Its Curie temperature is 355 °C (671 °F), meaning that majority nickel is non-magnetic above this temperature.[13] The unit of measurement prison cell of nickel is a face up-centered cube with the lattice parameter of 0.352 nm, giving an atomic radius of 0.124 nm. This crystal structure is stable to pressures of at least 70 GPa. Nickel belongs to the transition metals. Information technology is hard, malleable and ductile, and has a relatively high electrical and thermal conductivity for transition metals.[14] The high compressive strength of 34 GPa, predicted for ideal crystals, is never obtained in the real bulk material due to the formation and motion of dislocations. However, information technology has been reached in Ni nanoparticles.[fifteen]

Electron configuration dispute

The nickel atom has two electron configurations, [Ar] 3d8 4sii and [Ar] 3d9 4sone, which are very close in energy – the symbol [Ar] refers to the argon-like core structure. There is some disagreement on which configuration has the lowest energy.[sixteen] Chemical science textbooks quote the electron configuration of nickel as [Ar] 4s2 3dviii,[17] which tin can also exist written [Ar] 3dviii 4s2.[18] This configuration agrees with the Madelung energy ordering rule, which predicts that 4s is filled before 3d. Information technology is supported past the experimental fact that the lowest energy state of the nickel atom is a 3deight 4stwo energy level, specifically the 3d8(3F) 4s2 3F, J = 4 level.[nineteen]

Withal, each of these two configurations splits into several energy levels due to fine structure,[nineteen] and the two sets of free energy levels overlap. The boilerplate energy of states with configuration [Ar] 3dnine 4s1 is really lower than the average energy of states with configuration [Ar] 3d8 4s2. For this reason, the inquiry literature on diminutive calculations quotes the basis state configuration of nickel as [Ar] 3d9 4s1.[16]

Isotopes

The isotopes of nickel range in diminutive weight from 48 u ( 48

Ni) to 78 u ( 78

Ni).[ citation needed ]

Naturally occurring nickel is composed of v stable isotopes; 58

Ni, 60

Ni, 61

Ni, 62

Ni and 64

Ni, with 58

Ni beingness the most arable (68.077% natural abundance).[ citation needed ]

Nickel-62 has the highest mean nuclear binding energy per nucleon of any nuclide, at 8.7946 MeV/nucleon.[twenty] [21] Its binding energy is greater than both 56

Atomic number 26 and 58

Fe, more arable elements frequently incorrectly cited as having the virtually tightly bound nuclides.[22] Although this would seem to predict nickel-62 every bit the most abundant heavy element in the universe, the relatively high charge per unit of photodisintegration of nickel in stellar interiors causes iron to be by far the most arable.[22]

The stable isotope nickel-60 is the girl product of the extinct radionuclide sixty

Fe, which decays with a half-life of ii.6 meg years. Because 60

Iron has such a long half-life, its persistence in materials in the Solar System may generate appreciable variations in the isotopic limerick of 60

Ni. Therefore, the abundance of 60

Ni present in extraterrestrial fabric may provide insight into the origin of the Solar System and its early history.[ citation needed ]

At least 26 nickel radioisotopes have been characterised, the nigh stable being 59

Ni with a one-half-life of 76,000 years, 63

Ni with 100 years, and 56

Ni with 6 days. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are less than 60 hours and the majority of these have half-lives that are less than 30 seconds. This element also has i meta land.[23]

Radioactive nickel-56 is produced past the silicon burning process and later set free in large quantities during type Ia supernovae. The shape of the light curve of these supernovae at intermediate to tardily-times corresponds to the decay via electron capture of nickel-56 to cobalt-56 and ultimately to fe-56.[24] Nickel-59 is a long-lived cosmogenic radionuclide with a half-life of 76,000 years. 59

Ni has institute many applications in isotope geology. 59

Ni has been used to date the terrestrial age of meteorites and to make up one's mind abundances of extraterrestrial dust in ice and sediment. Nickel-78'due south half-life was recently measured at 110 milliseconds, and is believed an of import isotope in supernova nucleosynthesis of elements heavier than iron.[25] The nuclide 48Ni, discovered in 1999, is the virtually proton-rich heavy element isotope known. With 28 protons and 20 neutrons, 48Ni is "doubly magic", as is 78

Ni with 28 protons and 50 neutrons. Both are therefore unusually stable for nuclides with so large a proton–neutron imbalance.[23] [26]

Nickel-63 is a contaminant found in the back up structure of nuclear reactors. It is produced through neutron capture past nickel-62. Small amounts have also been found nigh nuclear weapon test sites in the South Pacific.[27]

Occurrence

Widmanstätten design showing the two forms of nickel-atomic number 26, kamacite and taenite, in an octahedrite meteorite

On World, nickel occurs well-nigh often in combination with sulfur and iron in pentlandite, with sulfur in millerite, with arsenic in the mineral nickeline, and with arsenic and sulfur in nickel galena.[28] Nickel is unremarkably establish in iron meteorites as the alloys kamacite and taenite. The presence of nickel in meteorites was first detected in 1799 past Joseph-Louis Proust, a French chemist who so worked in Kingdom of spain. Proust analyzed samples of the meteorite from Campo del Cielo (Argentina), which had been obtained in 1783 by Miguel Rubín de Celis, discovering the presence in them of nickel (nigh 10%) along with iron.[29]

The bulk of the nickel is mined from two types of ore deposits. The get-go is laterite, where the primary ore mineral mixtures are nickeliferous limonite, (Fe,Ni)O(OH), and garnierite (a mixture of diverse hydrous nickel and nickel-rich silicates). The 2nd is magmatic sulfide deposits, where the principal ore mineral is pentlandite: (Ni,Fe)

nine Southward

8 .[ citation needed ]

Republic of indonesia and Australia accept the biggest estimated reserves, at 43.6% of globe'southward total.[30]

Identified land-based resource throughout the world averaging one% nickel or greater contain at to the lowest degree 130 million tons of nickel (near the double of known reserves). Virtually 60% is in laterites and 40% in sulfide deposits.[31]

On geophysical show, nearly of the nickel on Globe is believed to be in the World's outer and inner cores. Kamacite and taenite are naturally occurring alloys of iron and nickel. For kamacite, the alloy is usually in the proportion of 90:x to 95:v, although impurities (such equally cobalt or carbon) may be nowadays, while for taenite the nickel content is between 20% and 65%. Kamacite and taenite are also institute in nickel iron meteorites.[32]

Compounds

The nearly common oxidation state of nickel is +two, just compounds of Ni0, Ni+, and Ni3+ are well known, and the exotic oxidation states Ni2−, Niane−, and Niiv+ have been produced and studied.[33]

Nickel(0)

Nickel tetracarbonyl (Ni(CO)

4 ), discovered past Ludwig Mond,[34] is a volatile, highly toxic liquid at room temperature. On heating, the complex decomposes back to nickel and carbon monoxide:

- Ni(CO)

iv ⇌ Ni + 4 CO

This behavior is exploited in the Mond process for purifying nickel, every bit described to a higher place. The related nickel(0) complex bis(cyclooctadiene)nickel(0) is a useful catalyst in organonickel chemistry because the cyclooctadiene (or cod) ligands are easily displaced.

Nickel(I)

Structure of [Ni

ii (CN)

half-dozen ] iv−

ion[35]

Nickel(I) complexes are uncommon, only one example is the tetrahedral complex NiBr(PPh3)3. Many nickel(I) complexes characteristic Ni-Ni bonding, such as the dark red diamagnetic K

iv [Ni

2 (CN)

six ] prepared by reduction of K

2 [Ni

2 (CN)

half dozen ] with sodium constructing. This chemical compound is oxidised in water, liberating H

2 .[35]

It is thought that the nickel(I) oxidation state is important to nickel-containing enzymes, such equally [NiFe]-hydrogenase, which catalyzes the reversible reduction of protons to H

ii .[36]

Nickel(II)

Colour of various Ni(II) complexes in aqueous solution. From left to right, [Ni(NH

three )

6 ] 2+

, [Ni(C2Hfour(NHii)ii)]2+, [NiCl

four ] two−

, [Ni(H

2 O)

6 ] 2+

Nickel(II) forms compounds with all mutual anions, including sulfide, sulfate, carbonate, hydroxide, carboxylates, and halides. Nickel(II) sulfate is produced in large quantities by dissolving nickel metal or oxides in sulfuric acid, forming both a hexa- and heptahydrates[37] useful for electroplating nickel. Common salts of nickel, such every bit chloride, nitrate, and sulfate, dissolve in h2o to requite green solutions of the metal aquo complex [Ni(H

two O)

six ] 2+

.[38]

The four halides form nickel compounds, which are solids with molecules that characteristic octahedral Ni centres. Nickel(II) chloride is most common, and its behavior is illustrative of the other halides. Nickel(2) chloride is produced by dissolving nickel or its oxide in muriatic acid. It is usually encountered as the light-green hexahydrate, the formula of which is ordinarily written NiCl2•6H2O. When dissolved in water, this table salt forms the metal aquo complex [Ni(H

two O)

6 ] 2+

. Aridity of NiClii•6HiiO gives the xanthous anhydrous NiCl

2 .[ citation needed ]

Some tetracoordinate nickel(II) complexes, east.g. bis(triphenylphosphine)nickel chloride, exist both in tetrahedral and foursquare planar geometries. The tetrahedral complexes are paramagnetic, whereas the square planar complexes are diamagnetic. In having properties of magnetic equilibrium and formation of octahedral complexes, they dissimilarity with the divalent complexes of the heavier group 10 metals, palladium(II) and platinum(II), which form only foursquare-planar geometry.[33]

Nickelocene is known; it has an electron count of 20, making information technology relatively unstable.[ commendation needed ]

Nickel(Three) and (IV)

Numerous Ni(Iii) compounds are known, with the offset such examples being Nickel(III) trihalophosphines (NiIii(PPh3)X3).[39] Further, Ni(Three) forms simple salts with fluoride[xl] or oxide ions. Ni(III) tin be stabilized past σ-donor ligands such every bit thiols and organophosphines.[35]

Ni(IV) is present in the mixed oxide BaNiO

three , while Ni(Three) is present in nickel oxide hydroxide, which is used every bit the cathode in many rechargeable batteries, including nickel-cadmium, nickel-iron, nickel hydrogen, and nickel-metal hydride, and used past certain manufacturers in Li-ion batteries.[41] Ni(IV) remains a rare oxidation state of nickel and very few compounds are known to date.[42] [43] [44] [45]

History

Considering the ores of nickel are easily mistaken for ores of silver and copper, agreement of this metallic and its use dates to relatively recent times. However, the unintentional use of nickel is ancient, and can be traced back as far as 3500 BCE. Bronzes from what is now Syrian arab republic have been found to contain as much every bit 2% nickel.[46] Some ancient Chinese manuscripts propose that "white copper" (cupronickel, known equally baitong) was used there between 1700 and 1400 BCE. This Paktong white copper was exported to Britain as early every bit the 17th century, but the nickel content of this blend was not discovered until 1822.[47] Coins of nickel-copper alloy were minted by the Bactrian kings Agathocles, Euthydemus 2, and Pantaleon in the second century BCE, possibly out of the Chinese cupronickel.[48]

In medieval Germany, a metallic yellow mineral was establish in the Erzgebirge (Ore Mountains) that resembled copper ore. Even so, when miners were unable to extract whatever copper from it, they blamed a mischievous sprite of German mythology, Nickel (similar to Old Nick), for besetting the copper. They called this ore Kupfernickel from the German Kupfer for copper.[49] [50] [51] [52] This ore is at present known as the mineral nickeline (formerly niccolite [53]), a nickel arsenide. In 1751, Baron Axel Fredrik Cronstedt tried to extract copper from kupfernickel at a cobalt mine in the Swedish village of Los, and instead produced a white metal that he named nickel afterwards the spirit that had given its name to the mineral.[54] In modern German language, Kupfernickel or Kupfer-Nickel designates the alloy cupronickel.[14]

Originally, the only source for nickel was the rare Kupfernickel. Outset in 1824, nickel was obtained equally a byproduct of cobalt bluish product. The first large-scale smelting of nickel began in Kingdom of norway in 1848 from nickel-rich pyrrhotite. The introduction of nickel in steel product in 1889 increased the demand for nickel, and the nickel deposits of New Caledonia, discovered in 1865, provided nearly of the world's supply between 1875 and 1915. The discovery of the large deposits in the Sudbury Basin, Canada in 1883, in Norilsk-Talnakh, Russian federation in 1920, and in the Merensky Reef, South Africa in 1924, fabricated large-scale production of nickel possible.[47]

Coinage

Aside from the aforementioned Bactrian coins, nickel was non a component of coins until the mid-19th century.[ commendation needed ]

Canada

99.9% nickel five-cent coins were struck in Canada (the world'southward largest nickel producer at the fourth dimension) during non-war years from 1922 to 1981; the metal content made these coins magnetic.[55] During the wartime period 1942–1945, near or all nickel was removed from Canadian and US coins to salvage it for manufacturing armor.[50] [56] Canada used 99.9% nickel from 1968 in its higher-value coins until 2000.[ commendation needed ]

Switzerland

Coins of nearly pure nickel were first used in 1881 in Switzerland.[57]

Great britain

Birmingham forged nickel coins in c. 1833 for trading in Malaysia.[58]

United States

In the United States, the term "nickel" or "nick" originally applied to the copper-nickel Flying Eagle cent, which replaced copper with 12% nickel 1857–58, and then the Indian Head cent of the same alloy from 1859 to 1864. Withal after, in 1865, the term designated the three-cent nickel, with nickel increased to 25%. In 1866, the five-cent shield nickel (25% nickel, 75% copper) appropriated the designation. Along with the alloy proportion, this term has been used to the nowadays in the United States.[ citation needed ]

Current use

In the 21st century, the loftier toll of nickel has led to some replacement of the metal in coins around the earth. Coins still made with nickel alloys include 1- and two-euro coins, 5¢, 10¢, 25¢, 50¢, and $ane U.South. coins,[59] and 20p, 50p, £1, and £two UK coins. From 2012 on the nickel-alloy used for 5p and 10p U.k. coins was replaced with nickel-plated steel. This ignited a public controversy regarding the problems of people with nickel allergy.[57]

Earth production

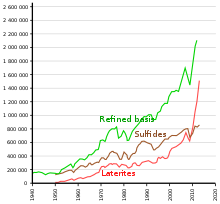

Time trend of nickel production[60]

Nickel ores grade evolution in some leading nickel producing countries.

More than 2.5 million tonnes (t) of nickel per year are estimated to be mined worldwide, with Indonesia (760,000 t), the Philippines (320,000 t), Russian federation (280,000 t), New Caledonia (200,000 t), Australia (170,000 t) and Canada (150,000 t) being the largest producers as of 2020.[61] The largest deposits of nickel in non-Russian Europe are located in Finland and Greece. Identified land-based resource averaging 1% nickel or greater contain at to the lowest degree 130 million tonnes of nickel. Approximately lx% is in laterites and forty% is in sulfide deposits. In addition, extensive nickel sources are institute in the depths of the Pacific Bounding main, particularly inside an expanse called the Clarion Clipperton Zone in the grade of polymetallic nodules peppering the seafloor at a depth of iii.v–six km below body of water level.[62] [63] These nodules are composed of numerous rare-earth metals and the nickel composition of these nodules is estimated to be 1.7%.[64] With advances in modern science and engineering, regulation is currently being ready in place by the International Seabed Potency to ensure that these nodules are collected in an environmentally conscientious style while adhering to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.[65]

The i locality in the United states where nickel has been profitably mined is Riddle, Oregon, where several square miles of nickel-bearing garnierite surface deposits are located. The mine closed in 1987.[66] [67] The Eagle mine project is a new nickel mine in Michigan's upper peninsula. Structure was completed in 2013, and operations began in the 3rd quarter of 2014.[68] In the first total year of operation, the Eagle Mine produced xviii,000 t.[68]

Production

Development of the annual nickel extraction, co-ordinate to ores.

Nickel is obtained through extractive metallurgy: information technology is extracted from the ore by conventional roasting and reduction processes that yield a metal of greater than 75% purity. In many stainless steel applications, 75% pure nickel can be used without further purification, depending on the impurities.[ citation needed ]

Traditionally, most sulfide ores have been candy using pyrometallurgical techniques to produce a matte for further refining. Recent advances in hydrometallurgical techniques resulted in significantly purer metallic nickel production. Most sulfide deposits have traditionally been candy past concentration through a froth flotation process followed past pyrometallurgical extraction. In hydrometallurgical processes, nickel sulfide ores are concentrated with flotation (differential flotation if Ni/Iron ratio is also low) and and then smelted. The nickel matte is further candy with the Sherritt-Gordon process. First, copper is removed by adding hydrogen sulfide, leaving a concentrate of cobalt and nickel. Then, solvent extraction is used to carve up the cobalt and nickel, with the final nickel content greater than 99%.[ citation needed ]

Electrorefining

A second common refining process is leaching the metal matte into a nickel salt solution, followed by the electrowinning of the nickel from solution past plating it onto a cathode as electrolytic nickel.[69]

Mond procedure

The purest metal is obtained from nickel oxide by the Mond process, which achieves a purity of greater than 99.99%.[seventy] The procedure was patented by Ludwig Mond and has been in industrial apply since before the beginning of the 20th century. In this process, nickel is reacted with carbon monoxide in the presence of a sulfur goad at effectually 40–80 °C to form nickel carbonyl. Iron gives iron pentacarbonyl, as well, merely this reaction is slow. If necessary, the nickel may be separated by distillation. Dicobalt octacarbonyl is as well formed in nickel distillation as a by-product, but it decomposes to tetracobalt dodecacarbonyl at the reaction temperature to give a non-volatile solid.[71]

Nickel is obtained from nickel carbonyl past ane of two processes. It may be passed through a big sleeping accommodation at loftier temperatures in which tens of thousands of nickel spheres, called pellets, are constantly stirred. The carbonyl decomposes and deposits pure nickel onto the nickel spheres. In the alternate procedure, nickel carbonyl is decomposed in a smaller chamber at 230 °C to create a fine nickel powder. The byproduct carbon monoxide is recirculated and reused. The highly pure nickel product is known every bit "carbonyl nickel".[72]

Metal value

The market price of nickel surged throughout 2006 and the early months of 2007; as of April five, 2007, the metal was trading at US$52,300/tonne or $1.47/oz.[73] The cost subsequently vicious dramatically, and as of September 2017, the metal was trading at $11,000/tonne, or $0.31/oz.[74]

The United states of america nickel coin contains 0.04 ounces (ane.1 thousand) of nickel, which at the April 2007 price was worth 6.5 cents, along with 3.75 grams of copper worth most 3 cents, with a total metal value of more than 9 cents. Since the face value of a nickel is 5 cents, this made it an attractive target for melting past people wanting to sell the metals at a profit. However, the United States Mint, in anticipation of this practice, implemented new acting rules on December 14, 2006, bailiwick to public comment for 30 days, which criminalized the melting and export of cents and nickels.[75] Violators tin can be punished with a fine of up to $10,000 and/or imprisoned for a maximum of five years.[76]

As of September 19, 2013, the melt value of a The states nickel (copper and nickel included) is $0.045, which is 90% of the face value.[77]

Applications

Nickel foam (top) and its internal structure (lesser)

The global production of nickel is presently used as follows: 68% in stainless steel; 10% in nonferrous alloys; ix% in electroplating; vii% in alloy steel; 3% in foundries; and 4% other uses (including batteries).[8]

Nickel is used in many specific and recognizable industrial and consumer products, including stainless steel, alnico magnets, coinage, rechargeable batteries, electric guitar strings, microphone capsules, plating on plumbing fixtures,[78] and special alloys such as permalloy, elinvar, and invar. It is used for plating and as a dark-green tint in glass. Nickel is preeminently an alloy metal, and its chief use is in nickel steels and nickel cast irons, in which it typically increases the tensile forcefulness, toughness, and elastic limit. Information technology is widely used in many other alloys, including nickel brasses and bronzes and alloys with copper, chromium, aluminium, pb, cobalt, silver, and golden (Inconel, Incoloy, Monel, Nimonic).[69]

A "horseshoe magnet" made of alnico nickel alloy.

Because it is resistant to corrosion, nickel was occasionally used equally a substitute for decorative argent. Nickel was also occasionally used in some countries after 1859 as a cheap coinage metal (encounter above), just in the later years of the 20th century, it was replaced past cheaper stainless steel (i.e. fe) alloys, except in the The states and Canada.[ citation needed ]

Nickel is an fantabulous alloying amanuensis for certain precious metals and is used in the fire assay every bit a collector of platinum group elements (PGE). As such, nickel is capable of fully collecting all half-dozen PGE elements from ores, and of partially collecting gold. High-throughput nickel mines may likewise appoint in PGE recovery (primarily platinum and palladium); examples are Norilsk in Russia and the Sudbury Basin in Canada.[ citation needed ]

Nickel foam or nickel mesh is used in gas diffusion electrodes for element of group i fuel cells.[79] [80]

Nickel and its alloys are frequently used every bit catalysts for hydrogenation reactions. Raney nickel, a finely divided nickel-aluminium alloy, is one common form, though related catalysts are as well used, including Raney-type catalysts.[ citation needed ]

Nickel is a naturally magnetostrictive textile, pregnant that, in the presence of a magnetic field, the fabric undergoes a small modify in length.[81] [82] The magnetostriction of nickel is on the order of 50 ppm and is negative, indicating that it contracts.[ citation needed ]

Nickel is used as a binder in the cemented tungsten carbide or hardmetal industry and used in proportions of vi% to 12% by weight. Nickel makes the tungsten carbide magnetic and adds corrosion-resistance to the cemented parts, although the hardness is less than those with a cobalt binder.[83]

63

Ni, with its half-life of 100.one years, is useful in krytron devices as a beta particle (loftier-speed electron) emitter to make ionization by the proceed-live electrode more reliable.[84] Information technology is being investigated equally a ability source for betavoltaic batteries.[85] [86]

Effectually 27% of all nickel production is destined for engineering, 10% for building and construction, 14% for tubular products, 20% for metallic goods, 14% for transport, 11% for electronic appurtenances, and 5% for other uses.[eight]

Raney nickel is widely used for hydrogenation of unsaturated oils to make margarine, and substandard margarine and leftover oil may contain nickel as contaminant. Forte et al. found that type ii diabetic patients have 0.89 ng/ml of Ni in the blood relative to 0.77 ng/ml in the control subjects.[87]

Biological role

Although it was not recognized until the 1970s, nickel is known to play an important office in the biological science of some plants, eubacteria, archaebacteria, and fungi.[88] [89] [90] Nickel enzymes such equally urease are considered virulence factors in some organisms.[91] [92] Urease catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea to form ammonia and carbamate.[89] [88] The NiFe hydrogenases can catalyze the oxidation of H

2 to form protons and electrons, and can besides catalyze the reverse reaction, the reduction of protons to form hydrogen gas.[89] [88] A nickel-tetrapyrrole coenzyme, cofactor F430, is present in methyl coenzyme M reductase, which can catalyze the formation of methane, or the contrary reaction, in methanogenic archaea (in +ane oxidation country).[93] One of the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase enzymes consists of an Iron-Ni-S cluster.[94] Other nickel-bearing enzymes include a rare bacterial course of superoxide dismutase[95] and glyoxalase I enzymes in bacteria and several parasitic eukaryotic trypanosomal parasites[96] (in higher organisms, including yeast and mammals, this enzyme contains divalent Zn2+).[97] [98] [99] [100] [101]

Dietary nickel may affect human health through infections past nickel-dependent bacteria, but information technology is besides possible that nickel is an essential food for bacteria residing in the large intestine, in effect functioning as a prebiotic.[102] The US Found of Medicine has non confirmed that nickel is an essential nutrient for humans, so neither a Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) nor an Acceptable Intake take been established. The Tolerable Upper Intake Level of dietary nickel is thousand µg/twenty-four hours as soluble nickel salts. Dietary intake is estimated at lxx to 100 µg/day, with less than 10% captivated. What is absorbed is excreted in urine.[103] Relatively large amounts of nickel – comparable to the estimated average ingestion above – leach into food cooked in stainless steel. For example, the amount of nickel leached afterwards ten cooking cycles into one serving of tomato sauce averages 88 µg.[104] [105]

Nickel released from Siberian Traps volcanic eruptions is suspected of profitable the growth of Methanosarcina, a genus of euryarchaeote archaea that produced methane during the Permian–Triassic extinction event, the biggest extinction event on record.[106]

Toxicity

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

| Pictograms |    |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H317, H351, H372, H412 |

| Precautionary statements | P201, P202, P260, P264, P270, P272, P273, P280, P302+P352, P308+P313, P333+P313, P363, P405, P501 [107] |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2 0 0 |

The major source of nickel exposure is oral consumption, as nickel is essential to plants.[108] Nickel is constitute naturally in the surround: Typical background concentrations do not exceed xx ng/g3 in the atmosphere; 100 mg/kg in soil; 10 mg/kg in vegetation; ten μg/L in freshwater and ane μg/50 in seawater.[109] Environmental concentrations of nickel may be increased past human pollution. For example, nickel-plated faucets may contaminate water and soil; mining and smelting may dump nickel into waste-water; nickel–steel blend cookware and nickel-pigmented dishes may release nickel into food. The temper may be polluted by nickel ore refining and fossil fuel combustion. Humans may blot nickel straight from tobacco fume and skin contact with jewelry, shampoos, detergents, and coins. A less-common form of chronic exposure is through hemodialysis as traces of nickel ions may be absorbed into the plasma from the chelating activeness of albumin.[ commendation needed ]

The average daily exposure does not pose a threat to homo health. Virtually of the nickel absorbed every day by humans is removed by the kidneys and passed out of the body through urine or is eliminated through the gastrointestinal tract without being absorbed. Nickel is not a cumulative poison, but larger doses or chronic inhalation exposure may be toxic, fifty-fifty carcinogenic, and constitute an occupational gamble.[110]

Nickel compounds are classified as human carcinogens[111] [112] [113] [114] based on increased respiratory cancer risks observed in epidemiological studies of sulfidic ore refinery workers.[115] This is supported by the positive results of the NTP bioassays with Ni sub-sulfide and Ni oxide in rats and mice.[116] [117] The human and brute information consistently indicate a lack of carcinogenicity via the oral route of exposure and limit the carcinogenicity of nickel compounds to respiratory tumours after inhalation.[118] [119] Nickel metal is classified as a suspect carcinogen;[111] [112] [113] in that location is consistency between the absenteeism of increased respiratory cancer risks in workers predominantly exposed to metal nickel[115] and the lack of respiratory tumours in a rat lifetime inhalation carcinogenicity study with nickel metal pulverization.[120] In the rodent inhalation studies with various nickel compounds and nickel metal, increased lung inflammations with and without bronchial lymph node hyperplasia or fibrosis were observed.[114] [116] [120] [121] In rat studies, oral ingestion of water-soluble nickel salts tin trigger perinatal mortality effects in significant animals.[122] Whether these effects are relevant to humans is unclear as epidemiological studies of highly exposed female workers take not shown adverse developmental toxicity effects.[123] [124] [125] [126]

People can exist exposed to nickel in the workplace by inhalation, ingestion, and contact with peel or eye. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for the workplace at 1 mg/m3 per viii-hour workday, excluding nickel carbonyl. The National Institute for Occupational Safe and Health (NIOSH) specifies the recommended exposure limit (REL) of 0.015 mg/miii per viii-hour workday. At 10 mg/miii, nickel is immediately unsafe to life and health.[127] Nickel carbonyl [Ni(CO)

4 ] is an extremely toxic gas. The toxicity of metal carbonyls is a function of both the toxicity of the metal and the off-gassing of carbon monoxide from the carbonyl functional groups; nickel carbonyl is also explosive in air.[128] [129]

Sensitized individuals may show a skin contact allergy to nickel known equally a contact dermatitis. Highly sensitized individuals may also react to foods with high nickel content.[130] Sensitivity to nickel may also be present in patients with pompholyx. Nickel is the top confirmed contact allergen worldwide, partly due to its use in jewelry for pierced ears.[131] Nickel allergies affecting pierced ears are often marked by itchy, red skin. Many earrings are now made without nickel or with depression-release nickel[132] to accost this problem. The amount allowed in products that contact homo pare is now regulated by the European Marriage. In 2002, researchers found that the nickel released past 1 and 2 Euro coins was far in excess of those standards. This is believed to be the result of a galvanic reaction.[133] Nickel was voted Allergen of the Yr in 2008 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.[134] In August 2015, the American Academy of Dermatology adopted a position statement on the safety of nickel: "Estimates suggest that contact dermatitis, which includes nickel sensitization, accounts for approximately $ane.918 billion and affects almost 72.29 million people."[130]

Reports show that both the nickel-induced activation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) and the up-regulation of hypoxia-inducible genes are caused past depletion of intracellular ascorbate. The improver of ascorbate to the culture medium increased the intracellular ascorbate level and reversed both the metal-induced stabilization of HIF-ane- and HIF-1α-dependent gene expression.[135] [136]

References

- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Nickel". CIAAW. 2007.

- ^ Pfirrmann, Stefan; Limberg, Christian; Herwig, Christian; Stößer, Reinhard; Ziemer, Burkhard (2009). "A Dinuclear Nickel(I) Dinitrogen Circuitous and its Reduction in Unmarried-Electron Steps". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 48 (18): 3357–61. doi:x.1002/anie.200805862. PMID 19322853.

- ^ Carnes, Matthew; Buccella, Daniela; Chen, Judy Y.-C.; Ramirez, Arthur P.; Turro, Nicholas J.; Nuckolls, Colin; Steigerwald, Michael (2009). "A Stable Tetraalkyl Complex of Nickel(Iv)". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 48 (ii): 290–4. doi:10.1002/anie.200804435. PMID 19021174.

- ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth West.; Nichols, Monte C., eds. (1990). "Nickel" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Vol. I. Chantilly, VA, United states of america: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN978-0962209703.

- ^ "Nickel: Nickel mineral information and information". Mindat.org. Archived from the original on March three, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ^ Stixrude, Lars; Waserman, Evgeny; Cohen, Ronald (November 1997). "Composition and temperature of Earth'southward inner core". Journal of Geophysical Research. 102 (B11): 24729–24740. Bibcode:1997JGR...10224729S. doi:x.1029/97JB02125.

- ^ Coey, J. M. D.; Skumryev, Five.; Gallagher, 1000. (1999). "Rare-earth metals: Is gadolinium really ferromagnetic?". Nature. 401 (6748): 35–36. Bibcode:1999Natur.401...35C. doi:x.1038/43363. S2CID 4383791.

- ^ a b c "Nickel Apply In Lodge". Nickel Institute. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017.

- ^ Treadgold, Tim. "Gold Is Hot But Nickel Is Hotter Equally Need Grows For Batteries In Electrical Vehicles". Forbes . Retrieved October xiv, 2020.

- ^ "Nickel Compounds – The Within Story". Nickel Institute. Archived from the original on August 31, 2018.

- ^ Mulrooney, Scott B.; Hausinger, Robert P. (June 1, 2003). "Nickel uptake and utilization by microorganisms". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 27 (2–3): 239–261. doi:10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00042-1. ISSN 0168-6445. PMID 12829270.

- ^ Shiozawa, Hidetsugu; Briones-Leon, Antonio; Domanov, Oleg; Zechner, Georg; et al. (2015). "Nickel clusters embedded in carbon nanotubes as high functioning magnets". Scientific Reports. v: 15033. Bibcode:2015NatSR...515033S. doi:10.1038/srep15033. PMC4602218. PMID 26459370.

- ^ Kittel, Charles (1996). Introduction to Solid State Physics. Wiley. p. 449. ISBN978-0-471-14286-7.

- ^ a b Hammond, C.R.; Lide, C. R. (2018). "The elements". In Rumble, John R. (ed.). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (99th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Printing. p. 4.22. ISBN9781138561632.

- ^ Sharma, A.; Hickman, J.; Gazit, N.; Rabkin, E.; Mishin, Y. (2018). "Nickel nanoparticles set a new tape of forcefulness". Nature Communications. 9 (one): 4102. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.4102S. doi:x.1038/s41467-018-06575-6. PMC6173750. PMID 30291239.

- ^ a b Scerri, Eric R. (2007). The periodic table: its story and its significance . Oxford University Press. pp. 239–240. ISBN978-0-nineteen-530573-9.

- ^ Miessler, G.50. and Tarr, D.A. (1999) Inorganic Chemistry 2nd ed., Prentice–Hall. p. 38. ISBN 0138418918.

- ^ Petrucci, R.H. et al. (2002) Full general Chemical science 8th ed., Prentice–Hall. p. 950. ISBN 0130143294.

- ^ a b NIST Atomic Spectrum Database Archived March 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine To read the nickel atom levels, blazon "Ni I" in the Spectrum box and click on Retrieve information.

- ^ Shurtleff, Richard; Derringh, Edward (1989). "The Most Tightly Jump Nuclei". American Journal of Physics. 57 (vi): 552. Bibcode:1989AmJPh..57..552S. doi:10.1119/1.15970. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved November nineteen, 2008.

- ^ "Nuclear synthesis". hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu . Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Fewell, Yard. P. (1995). "The diminutive nuclide with the highest mean bounden free energy". American Periodical of Physics. 63 (7): 653. Bibcode:1995AmJPh..63..653F. doi:10.1119/i.17828.

- ^ a b Audi, Georges; Bersillon, Olivier; Blachot, Jean; Wapstra, Aaldert Hendrik (2003), "The NorthUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties", Nuclear Physics A, 729: iii–128, Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A, doi:ten.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.eleven.001

- ^ Pagel, Bernard Ephraim Julius (1997). "Further burning stages: evolution of massive stars". Nucleosynthesis and chemical evolution of galaxies. pp. 154–160. ISBN978-0-521-55958-4.

- ^ Castelvecchi, Davide (April 22, 2005). "Atom Smashers Shed Low-cal on Supernovae, Big Bang". Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ^ Westward, P. (October 23, 1999). "Twice-magic metal makes its debut – isotope of nickel". Science News. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- ^ Carboneau, Grand. 50.; Adams, J. P. (1995). "Nickel-63". National Low-Level Waste product Management Programme Radionuclide Study Series. 10. doi:10.2172/31669.

- ^ National Pollutant Inventory – Nickel and compounds Fact Sheet Archived December 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Npi.gov.au. Retrieved on January ix, 2012.

- ^ Calvo, Miguel (2019). Construyendo la Tabla Periódica. Zaragoza, Spain: Prames. p. 118. ISBN978-84-8321-908-ix.

- ^ "Nickel reserves worldwide past country 2020". Statista . Retrieved March 29, 2021.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Kuck, Peter H. "Mineral Article Summaries 2019: Nickel" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Rasmussen, Chiliad. L.; Malvin, D. J.; Wasson, J. T. (1988). "Trace chemical element sectionalisation betwixt taenite and kamacite – Human relationship to the cooling rates of iron meteorites". Meteoritics. 23 (2): a107–112. Bibcode:1988Metic..23..107R. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.1988.tb00905.x.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (second ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ "The Extraction of Nickel from its Ores by the Mond Process". Nature. 59 (1516): 63–64. 1898. Bibcode:1898Natur..59...63.. doi:ten.1038/059063a0.

- ^ a b c Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. Yard. (2008). Inorganic Chemical science (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 729. ISBN978-0-13-175553-6.

- ^ Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2012). Inorganic Chemistry (4th ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 764. ISBN978-0273742753.

- ^ Lascelles, Keith; Morgan, Lindsay G.; Nicholls, David and Beyersmann, Detmar (2005) "Nickel Compounds" in Ullmann'south Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemical science. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_235.pub2

- ^ Academy Of Abuja; Av, Aderonke; Ah, Dede; Ai, Oluwatobi; Ne, Stephen (December 31, 2020). "A Review On The Metal Complex Of Nickel (Ii) Salicylhydroxamic Acid And Its Aniline Adduct". Journal of Translational Scientific discipline and Research. ii (1): 1–9. doi:10.24966/TSR-6899/100006. S2CID 212626015.

- ^ Jensen, Thou. A. (1936). "Zur Stereochemie des koordinativ vierwertigen Nickels". Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie. 229 (three): 265–281. doi:10.1002/zaac.19362290304.

- ^ Courtroom, T. L.; Dove, K. F. A. (1973). "Fluorine compounds of nickel(3)". Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions (nineteen): 1995. doi:10.1039/DT9730001995.

- ^ "Imara Corporation Launches; New Li-ion Battery Engineering for Loftier-Power Applications". Green Car Congress. December 18, 2008. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2009.

- ^ Spokoyny, Alexander M.; Li, Tina C.; Farha, Omar K.; Machan, Charles M.; She, Chunxing; Stern, Charlotte L.; Marks, Tobin J.; Hupp, Joseph T.; Mirkin, Chad A. (June 28, 2010). "Electronic Tuning of Nickel-Based Bis(dicarbollide) Redox Shuttles in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49 (31): 5339–5343. doi:10.1002/anie.201002181. PMID 20586090.

- ^ Hawthorne, Thousand. Frederick (1967). "(3)-i,2-Dicarbollyl Complexes of Nickel(III) and Nickel(Four)". Journal of the American Chemical Lodge. 89 (2): 470–471. doi:10.1021/ja00978a065.

- ^ Camasso, North. Yard.; Sanford, M. Southward. (2015). "Design, synthesis, and carbon-heteroatom coupling reactions of organometallic nickel(Iv) complexes". Science. 347 (6227): 1218–twenty. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1218C. CiteSeerX10.1.1.897.9273. doi:x.1126/scientific discipline.aaa4526. PMID 25766226. S2CID 206634533.

- ^ Baucom, E. I.; Drago, R. Southward. (1971). "Nickel(II) and nickel(Four) complexes of ii,6-diacetylpyridine dioxime". Journal of the American Chemic Society. 93 (24): 6469–6475. doi:10.1021/ja00753a022.

- ^ Rosenberg, Samuel J. (1968). Nickel and Its Alloys. National Bureau of Standards. [ permanent expressionless link ]

- ^ a b McNeil, Ian (1990). "The Emergence of Nickel". An Encyclopaedia of the History of Engineering. Taylor & Francis. pp. 96–100. ISBN978-0-415-01306-2.

- ^ Needham, Joseph; Wang, Ling; Lu, Gwei-Djen; Tsien, Tsuen-hsuin; Kuhn, Dieter and Golas, Peter J. (1974) Science and civilisation in China Archived May 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge University Printing. ISBN 0-521-08571-iii, pp. 237–250.

- ^ Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary, p888, West&R Chambers Ltd., 1977.

- ^ a b Baldwin, W. H. (1931). "The story of Nickel. I. How "Erstwhile Nick'southward" gnomes were outwitted". Journal of Chemical Teaching. eight (9): 1749. Bibcode:1931JChEd...8.1749B. doi:10.1021/ed008p1749.

- ^ Baldwin, W. H. (1931). "The story of Nickel. II. Nickel comes of historic period". Periodical of Chemical Education. 8 (10): 1954. Bibcode:1931JChEd...8.1954B. doi:10.1021/ed008p1954.

- ^ Baldwin, W. H. (1931). "The story of Nickel. III. Ore, matte, and metal". Periodical of Chemical Didactics. viii (12): 2325. Bibcode:1931JChEd...viii.2325B. doi:x.1021/ed008p2325.

- ^ Fleisher, Michael and Mandarino, Joel. Glossary of Mineral Species. Tucson, Arizona: Mineralogical Record, 7th ed. 1995.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The discovery of the elements: Iii. Some eighteenth-century metals". Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (i): 22. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9...22W. doi:10.1021/ed009p22.

- ^ "Industrious, enduring–the 5-cent coin". Royal Canadian Mint. 2008. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ Molloy, Bill (November 8, 2001). "Trends of Nickel in Coins – Past, Nowadays and Future". The Nickel Institute. Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ^ a b Lacey, Anna (June 22, 2013). "A bad penny? New coins and nickel allergy". BBC Wellness Bank check. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- ^ "nikkelen dubbele wapenstuiver Utrecht". nederlandsemunten.nl. Archived from the original on January seven, 2015. Retrieved Jan seven, 2015.

- ^ "Coin Specifications". usmint.gov . Retrieved October xiii, 2021.

- ^ Kelly, T. D.; Matos, Grand. R. "Nickel Statistics" (PDF). U.Due south. Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on Baronial 12, 2014. Retrieved August xi, 2014.

- ^ "Nickel Data Sheet - Mineral Commodity Summaries 2021" (PDF). US Geological Survey . Retrieved March 29, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Nickel" (PDF). U.Southward. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries. Jan 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved September xx, 2013.

- ^ Gazley, Michael F.; Tay, Stephie; Aldrich, Sean. "Polymetallic Nodules". Enquiry Gate. New Zealand Minerals Forum. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ Mero, J. L. (January 1, 1977). "Affiliate eleven Economic Aspects of Nodule Mining". Marine Manganese Deposits. Elsevier Oceanography Series. Vol. 15. pp. 327–355. doi:10.1016/S0422-9894(08)71025-0. ISBN9780444415240.

- ^ International Seabed Potency. "Strategic Program 2019-2023" (PDF). isa.org. International Seabed Authority. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ "The Nickel Mountain Project" (PDF). Ore Bin. fifteen (10): 59–66. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Surround Author: Nickel". National Rubber Council. 2006. Archived from the original on August 28, 2006. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ a b "Operations & Evolution". Lundin Mining Corporation. Archived from the original on November eighteen, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Davis, Joseph R. (2000). "Uses of Nickel". ASM Specialty Handbook: Nickel, Cobalt, and Their Alloys. ASM International. pp. seven–13. ISBN978-0-87170-685-0.

- ^ Mond, Fifty.; Langer, K.; Quincke, F. (1890). "Action of carbon monoxide on nickel". Periodical of the Chemical Society. 57: 749–753. doi:10.1039/CT8905700749.

- ^ Kerfoot, Derek M. Due east. "Nickel". Ullmann'south Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_157.

- ^ Neikov, Oleg D.; Naboychenko, Stanislav; Gopienko, Victor Grand & Frishberg, Irina V (Jan 15, 2009). Handbook of Non-Ferrous Metal Powders: Technologies and Applications. Elsevier. pp. 371–. ISBN978-1-85617-422-0. Archived from the original on May 29, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ^ "LME nickel price graphs". London Metal Exchange. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ "London Metal Exchange". LME.com. Archived from the original on September twenty, 2017.

- ^ U.s.a. Mint Moves to Limit Exportation & Melting of Coins Archived May 27, 2016, at the Wayback Automobile, The Us Mint, printing release, December 14, 2006

- ^ "Prohibition on the Exportation, Melting, or Treatment of 5-Cent and Ane-Cent Coins". Federal Annals. April 16, 2007. Retrieved Baronial 28, 2021.

- ^ "Us Circulating Coinage Intrinsic Value Table". Coininflation.com. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved September thirteen, 2013.

- ^ American Plumbing Exercise: From the Applied science Record (Prior to 1887 the Sanitary Engineer.) A Selected Reprint of Articles Describing Notable Plumbing Installations in the United states of america, and Questions and Answers on Problems Arising in Plumbing and House Draining. With Five Hundred and Thirty-six Illustrations. Applied science record. 1896. p. 119. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ^ Kharton, Vladislav V. (2011). Solid State Electrochemistry II: Electrodes, Interfaces and Ceramic Membranes. Wiley-VCH. pp. 166–. ISBN978-three-527-32638-9. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Bidault, F.; Brett, D. J. 50.; Middleton, P. H.; Brandon, N. P. "A New Cathode Design for Element of group i Fuel Cells (AFCs)" (PDF). Imperial College London. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011.

- ^ Magnetostrictive Materials Overview. Academy of California, Los Angeles.

- ^ Angara, Raghavendra (2009). High Frequency Loftier Amplitude Magnetic Field Driving System for Magnetostrictive Actuators. Umi Dissertation Publishing. p. 5. ISBN9781109187533.

- ^ Cheburaeva, R. F.; Chaporova, I. North.; Krasina, T. I. (1992). "Structure and properties of tungsten carbide hard alloys with an alloyed nickel binder". Soviet Powder Metallurgy and Metal Ceramics. 31 (5): 423–425. doi:10.1007/BF00796252. S2CID 135714029.

- ^ "Krytron Pulse Power Switching Tubes". Silicon Investigations. 2011. Archived from the original on July sixteen, 2011.

- ^ Uhm, Y. R.; et al. (June 2016). "Study of a Betavoltaic Battery Using Electroplated Nickel-63 on Nickel Foil every bit a Ability Source". Nuclear Applied science and Technology. 48 (iii): 773–777. doi:10.1016/j.cyberspace.2016.01.010.

- ^ Bormashov, V. Southward.; et al. (April 2018). "High power density nuclear battery epitome based on diamond Schottky diodes". Diamond and Related Materials. 84: 41–47. Bibcode:2018DRM....84...41B. doi:ten.1016/j.diamond.2018.03.006.

- ^ Khan, Abdul Rehman; Awan, Fazli Rabbi (January viii, 2014). "Metals in the pathogenesis of blazon 2 diabetes". Periodical of Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders. 13 (1): sixteen. doi:x.1186/2251-6581-xiii-xvi. PMC3916582. PMID 24401367.

- ^ a b c Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland M. O. Sigel, eds. (2008). Nickel and Its Surprising Impact in Nature. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. ii. Wiley. ISBN978-0-470-01671-viii.

- ^ a b c Sydor, Andrew; Zamble, Deborah (2013). Banci, Lucia (ed.). Nickel Metallomics: General Themes Guiding Nickel Homeostasis. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 375–416. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_11. ISBN978-94-007-5561-1. PMID 23595678.

- ^ Zamble, Deborah; Rowińska-Żyrek, Magdalena; Kozlowski, Henryk (2017). The Biological Chemistry of Nickel. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN978-i-78262-498-1.

- ^ Covacci, Antonello; Telford, John L.; Giudice, Giuseppe Del; Parsonnet, Julie; Rappuoli, Rino (May 21, 1999). "Helicobacter pylori Virulence and Genetic Geography". Scientific discipline. 284 (5418): 1328–1333. Bibcode:1999Sci...284.1328C. doi:10.1126/science.284.5418.1328. PMID 10334982. S2CID 10376008.

- ^ Cox, Gary M.; Mukherjee, Jean; Cole, Garry T.; Casadevall, Arturo; Perfect, John R. (February 1, 2000). "Urease equally a Virulence Factor in Experimental Cryptococcosis". Infection and Amnesty. 68 (2): 443–448. doi:x.1128/IAI.68.two.443-448.2000. PMC97161. PMID 10639402.

- ^ Stephen W., Ragdale (2014). "Affiliate 6. Biochemistry of Methyl-Coenzyme M Reductase: The Nickel Metalloenzyme that Catalyzes the Final Pace in Synthesis and the First Pace in Anaerobic Oxidation of the Greenhouse Gas Methyl hydride". In Peter M.H. Kroneck; Martha Eastward. Sosa Torres (eds.). The Metallic-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environs. Metallic Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 14. Springer. pp. 125–145. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_6. ISBN978-94-017-9268-four. PMID 25416393.

- ^ Wang, Vincent C.-C.; Ragsdale, Stephen W.; Armstrong, Fraser A. (2014). "Affiliate 4. Investigations of the Efficient Electrocatalytic Interconversions of Carbon Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide by Nickel-Containing Carbon Monoxide Dehydrogenases". In Peter M.H. Kroneck; Martha E. Sosa Torres (eds.). The Metallic-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. xiv. Springer. pp. 71–97. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_4. ISBN978-94-017-9268-four. PMC4261625. PMID 25416391.

- ^ Szilagyi, R. K.; Bryngelson, P. A.; Maroney, One thousand. J.; Hedman, B.; et al. (2004). "South G-Edge X-ray Assimilation Spectroscopic Investigation of the Ni-Containing Superoxide Dismutase Agile Site: New Structural Insight into the Mechanism". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 126 (10): 3018–3019. doi:10.1021/ja039106v. PMID 15012109.

- ^ Greig North; Wyllie S; Vickers TJ; Fairlamb AH (2006). "Trypanothione-dependent glyoxalase I in Trypanosoma cruzi". Biochemical Journal. 400 (two): 217–23. doi:10.1042/BJ20060882. PMC1652828. PMID 16958620.

- ^ Aronsson A-C; Marmstål E; Mannervik B (1978). "Glyoxalase I, a zinc metalloenzyme of mammals and yeast". Biochemical and Biophysical Inquiry Communications. 81 (4): 1235–1240. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(78)91268-8. PMID 352355.

- ^ Ridderström G; Mannervik B (1996). "Optimized heterologous expression of the human zinc enzyme glyoxalase I". Biochemical Journal. 314 (Pt ii): 463–467. doi:ten.1042/bj3140463. PMC1217073. PMID 8670058.

- ^ Saint-Jean AP; Phillips KR; Creighton DJ; Stone MJ (1998). "Active monomeric and dimeric forms of Pseudomonas putida glyoxalase I: evidence for 3D domain swapping". Biochemistry. 37 (29): 10345–10353. doi:10.1021/bi980868q. PMID 9671502.

- ^ Thornalley, P. J. (2003). "Glyoxalase I—structure, role and a disquisitional role in the enzymatic defence confronting glycation". Biochemical Club Transactions. 31 (Pt 6): 1343–1348. doi:10.1042/BST0311343. PMID 14641060.

- ^ Vander Jagt DL (1989). "Unknown affiliate championship". In D Dolphin; R Poulson; O Avramovic (eds.). Coenzymes and Cofactors VIII: Glutathione Part A. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- ^ Zambelli, Barbara; Ciurli, Stefano (2013). "Affiliate x. Nickel: and Homo Health". In Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland M. O. Sigel (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 321–357. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_10. ISBN978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470096.

- ^ Nickel. IN: Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Copper Archived September 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. National Academy Press. 2001, PP. 521–529.

- ^ Kamerud KL; Hobbie KA; Anderson KA (August 28, 2013). "Stainless Steel Leaches Nickel and Chromium into Foods During Cooking". Journal of Agricultural and Nutrient Chemical science. 61 (39): 9495–501. doi:10.1021/jf402400v. PMC4284091. PMID 23984718.

- ^ Flint GN; Packirisamy S (1997). "Purity of food cooked in stainless steel utensils". Nutrient Additives & Contaminants. fourteen (two): 115–26. doi:ten.1080/02652039709374506. PMID 9102344.

- ^ Schirber, Michael (July 27, 2014). "Microbe'southward Innovation May Have Started Largest Extinction Outcome on World". Space.com. Astrobiology Magazine. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

.... That spike in nickel immune methanogens to take off.

- ^ "Nickel 203904". Sigma Aldrich. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ Haber, Lynne T; Bates, Hudson K; Allen, Bruce C; Vincent, Melissa J; Oller, Adriana R (2017). "Derivation of an oral toxicity reference value for nickel". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 87: S1–S18. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2017.03.011. PMID 28300623.

- ^ Rieuwerts, John (2015). The Elements of Environmental Pollution. London and New York: Earthscan Routledge. p. 255. ISBN978-0-415-85919-6. OCLC 886492996.

- ^ Butticè, Claudio (2015). "Nickel Compounds". In Colditz, Graham A. (ed.). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Cancer and Society (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. pp. 828–831. ISBN9781483345734.

- ^ a b IARC (2012). "Nickel and nickel compounds" Archived September 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine in IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. Volume 100C. pp. 169–218..

- ^ a b Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on Classification, Labelling and Packaging of Substances and Mixtures, Alteration and Repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC and amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 [OJ L 353, 31.12.2008, p. 1]. Annex Half-dozen Archived March 14, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed July 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Globally Harmonised System of Nomenclature and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) Archived August 29, 2017, at the Wayback Car, fifth ed., Un, New York and Geneva, 2013..

- ^ a b National Toxicology Program. (2016). "Report on Carcinogens" Archived September 20, 2017, at the Wayback Auto, 14th ed. Research Triangle Park, NC: U.S. Section of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service..

- ^ a b "Report of the International Committee on Nickel Carcinogenesis in Human". Scandinavian Periodical of Work, Environment & Wellness. 16 (1 Spec No): i–82. 1990. doi:10.5271/sjweh.1813. JSTOR 40965957. PMID 2185539.

- ^ a b National Toxicology Program (1996). "NTP Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Nickel Subsulfide (CAS No. 12035-72-2) in F344 Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Inhalation Studies)". National Toxicology Programme Technical Report Serial. 453: 1–365. PMID 12594522.

- ^ National Toxicology Plan (1996). "NTP Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Nickel Oxide (CAS No. 1313-99-1) in F344 Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Inhalation Studies)". National Toxicology Program Technical Study Serial. 451: i–381. PMID 12594524.

- ^ Cogliano, V. J; Baan, R; Straif, Chiliad; Grosse, Y; Lauby-Secretan, B; El Ghissassi, F; Bouvard, V; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L; Guha, N; Freeman, C; Galichet, L; Wild, C. P (2011). "Preventable exposures associated with human cancers". JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Found. 103 (24): 1827–39. doi:x.1093/jnci/djr483. PMC3243677. PMID 22158127.

- ^ Heim, 1000. E; Bates, H. K; Rush, R. East; Oller, A. R (2007). "Oral carcinogenicity study with nickel sulfate hexahydrate in Fischer 344 rats". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 224 (2): 126–37. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2007.06.024. PMID 17692353.

- ^ a b Oller, A. R; Kirkpatrick, D. T; Radovsky, A; Bates, H. K (2008). "Inhalation carcinogenicity study with nickel metallic pulverisation in Wistar rats". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 233 (2): 262–75. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.08.017. PMID 18822311.

- ^ National Toxicology Programme (1996). "NTP Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Nickel Sulfate Hexahydrate (CAS No. 10101-97-0) in F344 Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Inhalation Studies)". National Toxicology Program Technical Written report Series. 454: 1–380. PMID 12587012.

- ^ Springborn Laboratories Inc. (2000). "An Oral (Gavage) Two-generation Reproduction Toxicity Written report in Sprague-Dawley Rats with Nickel Sulfate Hexahydrate." Final Written report. Springborn Laboratories Inc., Spencerville. SLI Written report No. 3472.iv.

- ^ Vaktskjold, A; Talykova, 50. 5; Chashchin, Five. P; Nieboer, E; Thomassen, Y; Odland, J. O (2006). "Genital malformations in newborns of female nickel-refinery workers". Scandinavian Periodical of Work, Environs & Health. 32 (1): 41–50. doi:10.5271/sjweh.975. PMID 16539171.

- ^ Vaktskjold, A; Talykova, L. 5; Chashchin, 5. P; Odland, Jon Ø; Nieboer, East (2008). "Spontaneous abortions among nickel-exposed female person refinery workers". International Periodical of Environmental Health Research. xviii (two): 99–115. doi:10.1080/09603120701498295. PMID 18365800. S2CID 24791972.

- ^ Vaktskjold, A; Talykova, Fifty. V; Chashchin, V. P; Odland, J. O; Nieboer, E (2007). "Pocket-sized-for-gestational-age newborns of female refinery workers exposed to nickel". International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 20 (4): 327–38. doi:ten.2478/v10001-007-0034-0. PMID 18165195. S2CID 1439478.

- ^ Vaktskjold, A; Talykova, L. V; Chashchin, 5. P; Odland, J. O; Nieboer, E (2008). "Maternal nickel exposure and congenital musculoskeletal defects". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 51 (11): 825–33. doi:10.1002/ajim.20609. PMID 18655106.

- ^ "CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemic Hazards – Nickel metallic and other compounds (every bit Ni)". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on July 18, 2017. Retrieved November twenty, 2015.

- ^ Stellman, Jeanne Mager (1998). Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety: Chemical, industries and occupations. International Labour Organisation. pp. 133–. ISBN978-92-two-109816-4. Archived from the original on May 29, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ^ Barceloux, Donald G.; Barceloux, Donald (1999). "Nickel". Clinical Toxicology. 37 (2): 239–258. doi:ten.1081/CLT-100102423. PMID 10382559.

- ^ a b Position Statement on Nickel Sensitivity Archived September 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. American Academy of Dermatology(August 22, 2015)

- ^ Thyssen J. P.; Linneberg A.; Menné T.; Johansen J. D. (2007). "The epidemiology of contact allergy in the full general population—prevalence and main findings". Contact Dermatitis. 57 (5): 287–99. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01220.x. PMID 17937743. S2CID 44890665.

- ^ Dermal Exposure: Nickel Alloys Archived February 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Nickel Producers Environmental Research Association (NiPERA), accessed 2016 Feb.11

- ^ Nestle, O.; Speidel, H.; Speidel, Thou. O. (2002). "High nickel release from 1- and 2-euro coins". Nature. 419 (6903): 132. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..132N. doi:x.1038/419132a. PMID 12226655. S2CID 52866209.

- ^ Dow, Lea (June 3, 2008). "Nickel Named 2008 Contact Allergen of the Yr". Nickel Allergy Information. Archived from the original on February three, 2009.